- Home

- D. B. Martin

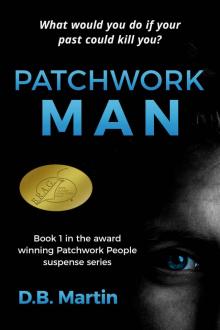

Patchwork Man: What would you do if your past could kill you? A mystery and suspense thriller. (Patchwork People series Book 1)

Patchwork Man: What would you do if your past could kill you? A mystery and suspense thriller. (Patchwork People series Book 1) Read online

PATCHWORK MAN

D.B. Martin

Published by IM Books

www.debrahmartin.co.uk

© Copyright D.B. Martin 2014

PATCHWORK MAN

All rights reserved.

The right of D.B. Martin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names and characters are a product of the author’s imaginations and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events and organisations is purely coincidental.

Condition of sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-0-9929961-2-3

“It is always the best policy to speak the truth – unless, of course, you are an exceptionally good liar.” Jerome K Jerome

Other books by this author:

Writing as D. B. Martin:

PATCHWORK MAN (Book 1) 2015 Winner of a B.R.A.G Medallion

Laurence Juste QC is the perfect barrister; respected, professional, always wins. But Lawrence Juste isn’t who he says he is, and his past is about to come back and haunt him...

PATCHWORK PEOPLE (Book 2)

No-one is what they appear to be, especially not Lawrence Juste QC. And no sooner does he patch one hole in his fraying life than another appears – unless his dead wife can help...

PATCHWORK PIECES (Book 3)

The wheel has turned full circle. The past is the present, the betrayed are the betrayers. Only a deadly form of natural justice can help Lawrence Juste, almost ex-QC, now...

Writing as Debrah Martin:

FALLING AWAKE

The story of Mary, Joe and a world populated by love, betrayal and obsession – and what it does to those who live in it. Fantasy or madness? The impossible is only a breath away.

CHAINED MELODIES

Courage isn’t about facing death, it’s about loving life – and life isn’t always conventional. The unusual story of how two men find not just courage, but self-belief and the true nature of love.

Writing as Lily Stuart (YA fiction):

WEBS

Meet Lily: one smart cookie with a bitchy BFF, moody boys and crazy school friends. Life’s a breeze by comparison to what happens when her mother starts internet dating with lethal results though. Step up Lily S: Teenage Detective.

MAGPIES

A boy with looks to die for – and Tourette’s – tricky BFFs, and and a gang of drug-dealers... THE teenage detective is back and looking for trouble – or trouble is looking for her. It finds her in the form of a childish rhyme, with a deadly hidden meaning.

Click here for your copy: http://eepurl.com/3-965

Contents

Prologue

1: Memories

2: The Case

3: The Boy

4: The Home

5: Innocence Lost

6: Jaggers

7: Danny

8: The Gutter

9: Solomon’s Wisdom

10: Win

11: Hidden Agendas

12: The Case for the Defence

13: Wild Card

14: Families

15: Little Mother

16: Sweet Charity

17: The Female of the Species

18: Medicine

19: Girls

20: Connections

21: Bonds

22: Circassian Circle

23: Patchwork People

24: Rough Justice

25: Atticus

26: Appearance

COMING SOON:

ABOUT D.B MARTIN

Prologue

Secrets.

They overwhelm you when you least want them to – like memories. You tuck them safely away and think they’re lost. They’re not. They’re merely lying dormant, awaiting the miscreant – inquisitive, prodding and delving.

I opened the envelope clumsily, exhausted from the effort of maintaining a dignified propriety since Margaret’s death yesterday. It was a list of names and dates and places, written in her hand. My hidden history, meticulously researched – including the parts I’d thought even I had forgotten. 1999 rolled back forty years to the first time the threads of my life unravelled, when I was nine, and a tidal wave of memories crashed over me in a suffocating arc of white water and humiliation. Then my body shook and the cold finger of fear slid down my neck and into my gut as the patchwork man felt his carefully seamed life pull apart.

1. Memories

It was 1959 and I was nine, the day everything changed. Nine, and puny. The aftermath of the Second World War was plain in my rationed frame and our meagre lifestyle, and the Croydon of then was a bomb-crumbled crater of dilapidated buildings and open spaces, perfect for kids to disappear in when they should be somewhere else. I can still remember it as if it were yesterday. I ran into the room, all skinned knees and flailing elbows, nose running from being outside in the crisp cold of early autumn. I recall even now hastily wiping it on the sleeve of my jumper so Ma wouldn’t chide me, and how the snot made a slimy snail trail. It sparkled in the morning sunlight, like someone had woven magic into the jumper’s holed and matted dereliction. I remember that almost more clearly than what the woman was saying.

‘You can’t carry on like this Mrs Juss.’ The woman was sitting on the only armchair we had; Pop’s chair, by the fire. She’d be for it if he came in. She looked as if she had a smell under her nose. Her bright red lips were stretched into a thin supercilious smile, and her nose wrinkled at Ma as if she was the one making the smell. I stopped in the doorway, mid-way between bursting in and running away. Was she here from the school? Telling Ma on me, and how I hadn’t been in weeks? Her legs were crossed daintily at the ankles but her ankles weren’t dainty at all. They were thick and bloated, like Mrs Fenner’s cat had been after it had died. It had blown up like a balloon and Ted Willis had poked it with a stick to see if it would pop. It hadn’t, it had just oozed pus and maggots and we’d watched fascinated but disgusted as the balloon had deflated and the sickly brown mess oozed out.

‘It were a nice ’un once,’ Ted had said to me. I hadn’t replied. I’d been too busy controlling the urge to retch over the yard wall, but I couldn’t forget too how it used to perch on the fence near the bins, stalking mice. It had been proud and feral then. Why did it have to turn into this?

I didn’t puke. Ted would have thought me a wimp, and told the others. Then Jonno and his mates would mark me as an easy target and tail me when I went down to Old Sal’s shop for Pop’s fags or a jug of milk for Ma, and grab whatever I’d got on me. They’d kick me in the guts for it too. Pop would belt me, and the buckle of his belt would leave a scratch from the spike. No, even as a child, I knew there were times when you had to feign indifference for appearances’ sake and keep your thoughts to yourself.

Instinctively I didn’t like the woman. Not just b

ecause her ankles reminded me of the cat, but because of the way she was talking to Ma. Ma looked so defeated. She was never like that with me. Sometimes she was as tough as old nails, hollering at me for being ‘a right little shit’ and whacking me across the knees with her wooden spoon. Other times she’d ruffle my hair and sigh. ‘Oh Kenny, whatever’ll I do with you; all of you,’ and I’d feel a surge of love for her that made me want to hug her tight and never let go because Ma just made you feel special when she did that.

‘What else can I do?’ Ma rounded on the woman harshly, a touch of her old spirit showing momentarily. Then she bent double with pain and gripped the back of the rickety chair that was hers at our dinner table.

‘Do you need the midwife?’ the woman asked anxiously, shifting awkwardly as if about to up and run herself.

‘Nah, I’ve had enough of them to know when it’s me time.’ Ma straightened up and saw me in the doorway. The woman saw me at the same time.

‘Is this one of them?’

‘This is my Kenny.’ Ma held a hand out towards me.

‘How old is he?’

‘I had him after Georgie so he must be nine or thereabouts.’ I wanted to say I’m here, and I can speak for meself, but I daren’t in case the woman was from the school. I studied Ma, trying to work out from her expression who the woman was, but it was blank. Worn out from childbirth and sheer grind I suppose by then.

‘Well, this one will make eleven Mrs Juss, and you can’t go on like this, whatever your religious beliefs. What school does Kenny go to? And why isn’t he there now?’ Ma looked at me, confused, and I felt like I’d betrayed her.

‘Which one do yer go to?’

‘The one down the end.’ My voice came out too loud. I couldn’t remember the name of it either. Shit.

‘So why aren’t you there, boy?’ The woman was addressing me now. I hung my head. She must be from the school. What was she here for otherwise? Now I was really for it. She turned her attention back to Ma. ‘Do you know why he isn’t at school, Mrs Juss?’ Ma shook her head slowly. ‘Do you know whether any of your children are at school right now?’ Ma shook her head again and flinched as another contraction cut her in two. The woman sighed loudly. ‘You have ten children, you’re about to produce another and yet you do not know where they are at any time during the day. I repeat, Mrs Juss: you cannot carry on like this.’ There was silence, broken only by Ma’s involuntary gasp.

‘It’s time,’ she croaked as she bent over, and her waters broke in a rush over the linoleum. The woman jumped up and grabbed me just before the blood-soiled puddle reached my feet, boot soles turning up at the ends where they were worn to splitting.

‘And what about your children?’

I tried to twist away from the woman. ‘Gerroff, you cow! Ma needs the midwife. Leggo and I’ll get her.’ I was afraid for Ma, but I wanted to escape as well. The woman’s nails cut into my shoulder but she let go and I stumbled forwards, almost ending up in the murky pool.

‘Go on then boy, hurry up.’ She waved me off impatiently. To Ma she said, ‘Where do you normally give birth, Mrs Juss – in here or on your bed?’ I didn’t hear Ma’s reply, I took to my heels and ran for Mrs Lapwood.

We kids were made to stay out in the yard as we all straggled back in from wherever we’d been – not at school; that was for sure. Binnie and Sarah looked after the littlest ones whilst the boys played footie and made catapults to ping stones at the crows. If we got one of them, they’d be tea, so it wasn’t just for mischief that we aimed at them. Upstairs the curtains were closed. Ma’s groans after I’d fetched the midwife were enough to keep me out, even if curiosity about what ‘give birth’, like the hoity-toity woman had called it, was actually all about. I’d never been this close to a new brother or sister appearing before. It had always happened whilst I’d been out somewhere. It wasn’t as if it was the first time, of course, but this time made it through the immunity that childhood usually provides. I didn’t want to see Ma’s contorted face, or hear those inhuman howls again. They had terrified me, even though I wouldn’t have admitted it to anyone. There was something no longer childish about my world that day.

About five hours later, bellies empty and limbs stiff from the insidious cold of the twilight of an autumn day, we were allowed to troop in and see the newest member of the family. It was scrawny and red-faced, screwed up and misshapen like one of Binnie’s ragdolls that had got mixed up with the red table cloth and come out of the wash deep pink, instead of white. The snooty woman turned out to be from The Authorities – as Pop put it. She was still there, and a bloke with small wire-rimmed glasses and a big folder under his arm had joined her. They were waiting in the corner of the room and counted us in. I didn’t like it. It made me feel like I was being herded. Ted had told me his uncle counted the sheep on his farm in before they went to the slaughter house. Ted had stayed there once, when his mother had rheumatic fever and he and his brothers and sisters were shipped off to the farm until she was better.

‘It were good,’ he’d informed me when he came back, grinning, ‘until they herded up all them little lambs and stuffed them onto a truck. You knew they was gonna get their gizzards slit – sshh,’ and he made a slicing action across his throat like it was being cut. I didn’t like the idea of herds after that or being counted in. It was probably what put me off school because I did like finding out things I hadn’t known before.

The man pushed between us as we filled the room, and separated us into two groups; the ones older than ten and the ones younger. I shuffled toward the older ones’ group, taking Georgie with me, but was kept back by the bloke. The older ones – three of them – were marshalled across to the woman with the bulging ankles. Pop was there too, looking stony-faced in his best trousers and a clean white shirt tucked behind his braces. With the ‘Authorities’ people there, the belt that I feared so much was redundant around his waist. We kids all knew what the belt was there for. Pop stuck his thumbs in it and slouched against the wall, scowling, as the bloke with the glasses and folder told us to sit on the floor. Jill sat on Binnie’s lap and Emm was on Sarah’s, curled into a little huddle like Binnie’s doll. Sarah was twelve and Binnie almost eleven. They bossed me about when they had the chance and I cheeked them back like the devil, but I think they were kind girls really. I wish I hadn’t pulled their hair and pinched them as spitefully as I had when they told me off now. There were times when they mopped my cuts and hugged me when it hurt, like little mothers. I remember those times with a regret it’s hard to shake, because I haven’t seen them again since that night – in all of forty years – over half an expected lifetime. They are a part of my past I might have still wanted around – once.

The fat-ankled woman subdivided us again. The girls went with her, apart from the two tiniest ones who were taken back to Ma. The woman took my older sisters into their bedroom – shared between the five of them, Binnie, Sarah, Mooney Mary as we called her – turned at birth, or so Ma Lapwood said, and Jill and Emm, the girl twins. The man took me, Pip and Jim into our room and told us to pack our clothes into small brown suitcases that were already placed on our beds, open and waiting. Win and Georgie were told what to do and left to it.

Pip and Jim sat either side of the suitcases, eyeing them and the man suspiciously. They were almost identical, but not quite. I could tell the difference because Pip had lost both his two front teeth at the time whereas Jim had only lost one, so it was easy to work out who was who. I always wonder why – given the fact that they enjoyed tricking everyone so much – Jim hadn’t already yanked out his extra tooth. Maybe I remember us all as both harder and more vulnerable than we were at the time? They were the lookers of our motley crew, sandy hair falling in wilful shocks round scrubbed-apple cheeks, freckles and bright blue eyes; tomboys with charm. I was just a scraped-kneed, stick-legged awkward version of them, with sallow cheeks, wary eyes and an apparently hard outer skin. Ironic that my hard outer skin was in reality softer than a baby’s, and

my heart easier hurt than a girl’s.

‘You’re going on a little trip, whilst your mother gets better after having this baby. It’s all too much for her to cope with all of you at the same time. It will be nice, you’ll see.’ He was quietly spoken and seemed sincere. I remembered Ted’s trip to stay with his uncle. I liked the sound of the wide open spaces, the animals, the fresh air and time to roam. He’d even said the village school they’d gone to was all right. No more Jonno and his gang, or Pop and his belt.

‘Ted went to stay with his uncle when his ma was poorly,’ I told the twins. ‘It’ll be OK, you’ll see.

‘Will we all be together?’ Pip asked shyly.

‘I’m sure it will all be sorted out satisfactorily,’ the man assured him, but looked away at his watch. ‘We really need to hurry up though. You have a train to catch.’

‘A train?’ Jim was agog. ‘I’ve never been on a train before. Is it a big un? Is it taking us somewhere good?’ The man looked at him reflectively.

‘Yes it is.’ He said eventually. He went to stand by the window and looked out, face half in shadow. ‘Come on, get a move on then,’ he threw back at us over his shoulder without turning round. I bundled what little I had in my suitcase as quickly as I could and then went over to him at the window. He was looking out at the grassy sides of the communal air-raid shelters that were still standing from the war. Ma occasionally told us stories of how cramped and stuffy it had been down them and what it had been like when the bombs fell. My oldest brother Win had been conceived the year the war officially ended and Ma had named him after Winston Churchill in honour: Winston Kenneth Lawrence Juss. She’d rearranged the names for me and Georgie had a similar combination. There was no denying the connection between us – that was sure.

The speed at which you could run down the slopes of the shelters depended on how confident you felt at the time. It was the way we tested who was top dog locally. Jonno was the current holder of the fastest time then so he and his gang were in charge. I’d always intended to beat him one day. I chalked up that particular race as one that would have to wait until I was older – maybe a good thing considering my skinny body and scrawny muscles. Occasional trips and falls did no real damage, but I had still to develop the ability to put my hands out in front of me as a cushion so I usually had a good assortment of bruises, after-effects of nose-bleeds and the occasional black eye as rewards for my practice runs. Ma obviously thought that I was often in fights and would exclaim wearily over me when I rolled in with another set of injuries. I tried once to tell her it was all innocent but she wasn’t listening. It never seemed to matter much after that, other than that I didn’t like her thinking I was in trouble all the time, when really I was anything but.

Patchwork Man: What would you do if your past could kill you? A mystery and suspense thriller. (Patchwork People series Book 1)

Patchwork Man: What would you do if your past could kill you? A mystery and suspense thriller. (Patchwork People series Book 1)